After deploying a steel-frame handgun for many years, I have come to appreciate lightweight (LW) frame handguns. Aluminum frame revolvers and self-loaders have become trusted companions. I am not one to save a few ounces at the cost of my life, but I do not wish to carry more weight than necessary.

A good handgun, holster and spare magazine, not to mention the knife and combat light, the weight can really add up. I won’t try to convince you that an aluminum frame handgun is as durable as steel, as light as some polymer offerings, or that the handguns are as easy to shoot well, but the trade-offs are acceptable. If you are both practical and serious concerning personal defense, you may come to the same conclusion I have: Aluminum-frame pistols make sense. You simply have to understand the breed, and the shooter must give his or her personal best to mastering this type of gun.

There are other lightweight alloys, but the most common and most suitable for personal defense handguns, such as the 1911, is aluminum. Aluminum was once a precious metal but advanced mining and processing techniques changed the world. After World War II, aluminum frame technology—developed for aircraft—changed the handgun world. Today, aluminum-frame handguns have a half-century service history—that’s unmatched by any other lightweight gunmetal. The aluminum-frame handgun is usually a doppelganger to the steel-frame pistol, identical in appearance but made of a different frame or receiver material.

The Colt Commander was among the first widely popular, lightweight frame handguns. It was similar to the Government Model but with a barrel and slide .75-inch shorter than the GI .45. The pistol weighs 28 ounces versus 39 for the Government Model 1911. The Smith & Wesson Chief’s Special was among the first new handguns to be offered in both steel-frame (Model 36) and aluminum-frame (Model 37) versions. These revolvers weigh 20 and 12 ounces, respectively.

Before guns such as these were developed and introduced, carrying an effective handgun meant carrying more weight. Gunsmiths cut down big bore revolvers and were moderately successful, but by and large, smaller guns were the norm for concealed carry. Those looking for a lighter carry gun were likely to choose a .32 or .380 automatic or a small-frame revolver.

The new breed of handguns introduced after World War II were as light or lighter than those small-caliber guns, but, they offered the power and reliability of their service-grade actions and cartridges. These handguns made it possible to be well armed with a degree of comfort—at least as far as carry is concerned. However, due to their light weight, aluminum-frame handguns exhibit more recoil than their steel-frame counterparts, and this increased recoil is the primary drawback.

In order to refresh my memory and validate my perceptions, I fired several handguns in preparation for this report. I fired both steel frame and aluminum frame .38 caliber revolvers and self-loading handguns in 9mm and .45 caliber. I believe, as a general rule, an aluminum-frame handgun requires about 25% more practice to achieve the same level of proficiency as a comparable steel-frame handgun. You must understand this rule and accept the fact that you’ll either have to practice more or be less capable. In my opinion, more shooters are poorly armed due to a lack of practice than incorrect handgun choices. Aluminum-frame handguns demand shooters who actually practice with their handguns.

Other Considerations

Sharp or rough edges are more likely to prove uncomfortable when recoil is heavier. When firing a revolver, it is common for shooters to receive cuts on the thumb from the cylinder latch. A self-loader’s action absorbs recoil in comparison to the revolver as the recoil spring brings the slide back smartly and aids in recoil control, if the pistol is properly sprung and regulated.

You must choose a revolver with an efficient rubber grip for control and comfort with heavy loads. A number of shooters have commented that a lightweight revolver bites with the first shot, while the autoloader sneaks up on you. The first few magazines fired in a lightweight 1911 are not uncomfortable, but after a long practice session, you will be rubbing your wrists. Be certain your practice sessions are well spent.

When firing the revolver, it is common for the knuckle of the third finger of the firing hand to be rapped by the trigger guard in recoil. Modern grips address this concern, and so does a proven technique. By extending the third finger to a position under the trigger guard, the rap may be avoided and control enhanced.

Only standard-pressure ammunition should be used in lightweight handguns. Even if the handgun might endure continued use of high-pressure loads, the lack of control from the extra recoil will be skirting the edge of acceptable limits—even for experienced shooters. Aluminum-frame semi-autos present a longer list of technical and mechanical considerations. GI-type grip tangs sometimes exhibit uncomfortably sharp edges.

Modern lightweight-frame pistols are equipped with beavertail grip safeties. This spreads recoil out rather than concentrating the recoil force in one area, prevents the gun from biting the hand, and subtly lowers the bore axis. The 1911 handgun is highly developed. The SIG P series and Beretta 92 semiautos also use aluminum frames. They are models of reliability.

Lightweight, 1911

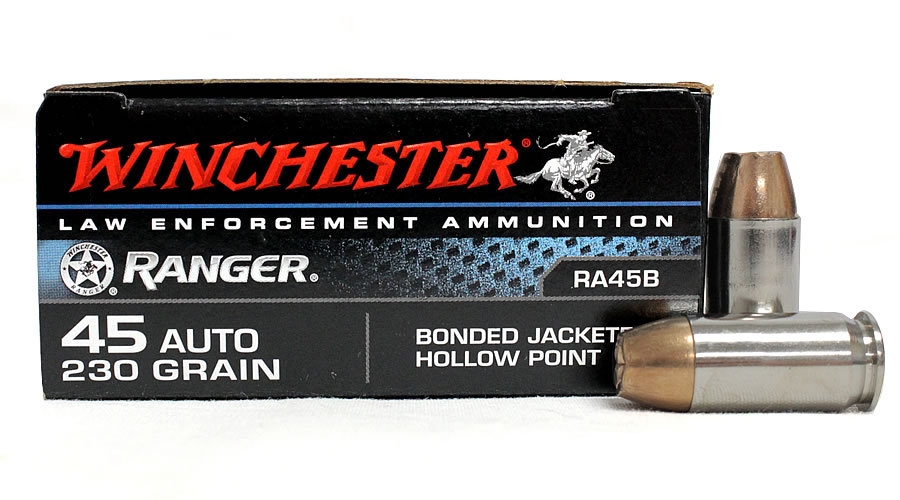

The 1911 is a controlled-feed handgun that keeps the cartridge under control of either the magazine lips or extractor during every stage of the feed cycle. Cartridges loaded to around the magic 1.250-inch overall cartridge length feed best. Cycle reliability is best served with 230-grain loads—the bullet weight for which the .45 ACP was designed. Winchester 230-grain SXT or 230-grain Bonded Core are excellent choices.

Modern, well-designed JHP loads cure a problem that has dogged the aluminum-frame 1911 handgun, because longevity and strength are not the same. An aluminum-frame service pistol may have the same service life as a steel-frame pistol. Either will withstand many thousands of rounds of ammunition. However, aluminum-frame handguns will not withstand abuse as well as a steel-frame handgun.

At one time, ammunition companies produced bullet shapes that required the feed ramp of the 1911 to be modified or throated, and quite a few 1911 handguns were subsequently throated by amateurs and resulted in disastrous consequences. Original design specifications called for a 1/32-inch gap between the frame ramp and barrel ramp. Even more importantly, the slight bump as the cartridge runs across the feed ramp serves to snug the cartridge into the extractor during the feed cycle.

The best solution has been to incorporate a ramped barrel into every aluminum-frame handgun. My Springfield Lightweight Loaded 1911 (which is 25 percent lighter than a steel-frame Loaded 1911) also features a ramped barrel. There is simply no concern about feed ramp damage with this design.

With a little attention, you may avoid the major disasters that occur with aluminum frames. As an example, take special care when disassembling an aluminum-frame pistol. If you detail-strip the pistol, prying the safety from the frame may damage the frame. Anytime one part is steel and the other a softer alloy, use special care.

The plunger tube is another concern. Be certain your grips properly support the plunger tube as per the original design. When you fieldstrip the pistol, snapping the slide lock back into lockup too sharply may stress the plunger tube and cause it to wallow in the frame. I have seen these problems, and they are difficult to repair. Avoid 10-thumbed handling, and your aluminum-frame handgun will stay the course.

Lightweight concealed carry handguns are a good choice, simply maintain the pistols and understand their limitations. Practice hard and learn the requirements of maintaining the handgun. Do this, and they will serve well.

Parting Thoughts on Service Pistols

Aluminum frame handguns are not simply for concealed carry. For home defense, service, and police use, the aluminum frame SIG P226, Beretta 92, and Colt LW frame Government Model are good choices—just to name a few of the classics. Durable? I doubt whether anyone even gives a second thought to the aluminum frame of the Beretta 92 or the SIG P226. I am pretty certain the single reason the CZ 75 isn’t as popular is because it is heavy.

What do you think of aluminum-framed handguns? Do you use one? Share your experiences in the comments section.

Sign up for K-Var’s weekly newsletter and discounts here.

Walther P1. Don’t carry it, but it is a cool nostalgic aluminum framed piece. Purported to be susceptible to cracking but it has been suggested that running 115gr standard loads through it that it will last a long time.